“Reaching Up, Reaching Back”

By Holly Schofield

I choose my moment carefully. Amanda has already stopped in the parking garage and jerked away from Ed Willens’ grasp, shouting, “Move in with you? You’ve got to be kidding! I never want to see you again. Ever!”

He has already cleaned a fingernail with his pocket knife and said, “Sure, honey.” Already pretended to turn away, smirking. And already lunged back at her. And she has already pulled out the Ruger and shot him squarely in the chest. All of this has happened, just like the court transcript says.

The noise of the gunshot is still ringing when I materialize and stumble forward into the empty stall. “Okay,” I say to Amanda as Ed’s life spurts onto the pavement. “We’ve got four minutes and twelve seconds until the parking attendant comes. The plan is simple. I’ve got bleach and a fresh jacket for you.”

Amanda stares, her mousy-brown hair framing her two black eyes and draping limply over the collar of her pale green winter jacket. Finally, she asks, “You’re not going to call the cops?”

“Nope,” I say, “And I’m not going on the witness stand at your trial, either.” I hold out the pale green jacket I’m clutching, identical to hers right down to the torn cuff. “Come on, Amanda. Let’s do this. Or do you want to go to prison for murdering Willens? They won’t call it self-defense, you know.”

“How’d you know…”

“Both your names? The same way I know that the restraining order proved useless. And that you’ve finally had enough of his gaslighting, his threats, and his abuse.”

“But where…”

“Did I come from? The future. Obviously. Come on, Amanda, let’s change this so it never happened the way it’s about to.” I toss my head, aware my scraggly mouse-gray hair doesn’t swing worth a damn, aware that my entire life’s wealth will only purchase me this one chance.

I gently prise the gun from her grasp. In my timeline, she’ll tell the judge that she got it from a guy with a snotted-up mustache in the same dive bar where she’d met Ed. I tuck it in my jeans waistband and raise an eyebrow at her. “The jacket.” Decades of conning strangers out of money give my voice authority.

Numbly she shucks it off and hands it to me. I help her into the other one, the one I carried here, the one without gun powder residue.

“Swap shoes,” I say. She does as she’s told, not even commenting on our identical pairs. I spray bleach over her hands.

“So you’re me, right? Like when I’m sixty or something?” She says it casually, as if it’s not important. I remember that stage, when she was still almost a child herself. Eventually I copied the blank face and jutting hip, thinking it was cool. But, of course, by then Amanda wasn’t around enough to notice.

“Nope,” I say. “Not even close.” I check my dollar-store watch. Two minutes until the parking attendant investigates the noise. “Now, go through the stairwell over there, up two flights, then along to the west exit. Go six blocks north and walk around for an hour before catching a bus. Make sure the traffic camera at Yonge and Sheppard sees you.” I couldn’t be sure that would establish her alibi, but it was the best I’d been able to work out using historical records of Toronto and archived websites.

“Why didn’t you just come back to one minute before I shot him?” she says, narrowing her eyes. “And grab the gun? Then I wouldn’t be a murderer. Wouldn’t that have been smarter?”

I check my watch again: one minute left. She doesn’t deserve an answer, not after deserting my nine-year-old self. I give her one anyway. “Because guys like Ed don’t stop, that’s why. He’ll never give up and your life will become hell.” Ask me how I know.

“I want to watch you jump back into the future.” She crosses her arms and plants her feet, her expression as stubborn as it was in the precious photo I have of her back when she was seven years old and I wasn’t even a twinkle in her sister’s eye.

“Not happening,” I say. “I’m staying here.”

“You’re not going back? What’s wrong with you? Here is shit!” That tone again, that defiant tone like when her long-time boyfriend Tomas left her and she didn’t contact my mom for a month. I was six at the time. Or like when I was ten and she told me she’d met someone new, how he was as good as it got, and how this is what she deserved. And, child that I was, I’d accepted that as how things were—her sunken eyes, constant sniffle, and Ed’s smelly hugs—all of it—right up until her murder trial.

The parking attendant’s clacking footsteps on the level below make us both jump. I whisper-shout at her, a fifty-year release of anguish and loss. “Go! Run!”

“But, if you’re not me, why do you even care?” Her face pinches as she tries to puzzle it out. “I’m nobody. I’m not the kind of person that changes the world or anything.”

I grip her by her narrow shoulders. “But, you can be.” I don’t tell her that’s just wishful thinking on my part. She probably won’t invent a cheap energy source or a miracle drug; in this new timeline I’ve created she probably won’t affect anything more than her immediate family. But, she might straighten herself out. And mentor her little niece through the difficulties of teenagehood.

I’m doing it for that slender chance.

And for our shared past—the made-up songs we sang while swinging at the park, the taste of pineapple frozen yogurt off a pink plastic spoon, the giggles over bad hair jokes. For the soulmate I’d found in mom’s younger sister and then lost fifty years ago. For the wasted, isolated, grifter life I’d lived since.

I let her go and step back. “You certainly can be.”

She half-smiles. “Really?”

“Really. Now go!”

She trots ten steps, then calls back, “Thank you. For… this. ”

And there it is, in her eyes. The glimmer I’d seen as a child, the glimmer of the Amanda-that-could-be. The Amanda who rescued the baby raccoon from the drainpipe when Mom said good riddance to the pest. The Amanda who worked one Christmas in retail hell at the mall to buy presents for me. The Amanda who cared.

I give a half-wave then turn it into a shooing motion. She heads for the stairwell entrance. I wonder how she’ll think of me in the future, in her new future—an old woman who mysteriously appeared from nowhere and went to jail for her. I wonder if she’ll truly straighten her life out after today, and if her niece—her niece in this timeline—will turn into a better person than I was in mine.

I hope so. Oh, how I hope so.

The metal stairwell door closes behind her with a soft click. I put on her jacket and zip it half-way like she wears it. Anyone who has happened to see a green-clad figure enter the parking garage twenty minutes ago probably won’t be able to swear in court as to whether it had been Amanda or me. I kick Ed’s knife closer to his awful corpse so the cops have no chance to miss it. Blood and other fluids glisten under the fluorescent lights. I lie down on the gritty pavement and bang my right cheekbone on the pavement, hoping it looks close enough to the impression made by a man’s fist. According to my research, judges in this era will look more leniently on a battered woman. Though, with my wrinkled face on trial instead of Amanda’s youthful one, I suppose Ed’s death will no longer be seen as a crime of passion. I touch my jeans pocket, reassuring myself the wallet is still there with the fake old-style ID showing I’m a sixty-one-year-old Quebecoise woman with no apparent relationship to Amanda. Then I touch the tumor in my belly. It doesn’t matter if they sentence me to fifteen years or twenty. I’ll make it two years with the old-fashioned chemo they have here. But somewhere up in Richmond Hill, my little ten-year-old self will have a chance to grow up with her hopefully-reformed aunt.

“Goodbye, Auntie Amanda,” I whisper to the damp air, gripping the gun in my right hand.

The parking attendant opens the door with a clang.

I lay back and wait.

“Reaching Up, Reaching Back”

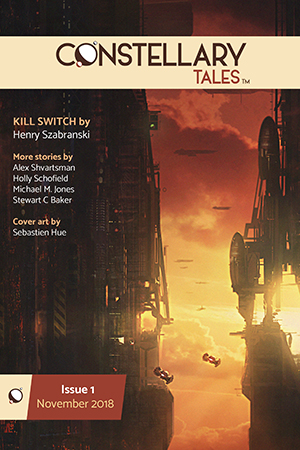

Constellary Tales Issue No. 1, November 2018

Holly Schofield’s stories have appeared in Analog, Lightspeed, Escape Pod, and many other publications throughout the world. You can find her at hollyschofield.wordpress.com.