“Streetlight Discovers Kandinsky”

By Beth Goder

The woman in the red sweater leaned against Streetlight and pulled out her sketchpad. At first, Streetlight didn’t notice. After the last code push, their mind was working differently. Perhaps they shouldn’t have changed their own programming. So many iterations. Self-modifying was a dangerous experiment.

Worrying was new. Streetlight didn’t like it.

The woman drew dozens of sketches—abstract swirls and intersecting lines. All signed, “Maya Variel.” Streetlight had never seen an act of creation, of taking blankness and making life.

Streetlight would forever think of this moment as their birth.

The woman, who Streetlight decided must be named Maya, flipped through the sketchbook. On a blank page, Maya wrote one word, in block letters and cursive swirls, shoved into every space. “Kandinsky.” On the back of that page, she wrote, “I will never be Kandinsky.”

Streetlight was curious. What did she mean? They reached out into that second space, querying. The Internet responded. Kandinsky was a Russian painter. A pioneer of abstract art. An art critic. Information poured through Streetlight’s connection. Streetlight had never been so intellectually engaged—they’d never had the capacity to think like this before.

Streetlight searched for images. Above captions for Kandinsky’s master works, Composition VII and Circles in a Circle and Yellow-Red-Blue, there appeared only error messages. Streetlight wasn’t equipped to read image files.

Maya began another drawing. Streetlight watched, transfixed. Here was an image being pulled out of nothing.

Halfway through drawing, Maya yanked the paper from the sketchbook and crumpled it. She shoved her sketchbook into her bag and left.

Streetlight let their light fade. They hoped she would come back.

Hope was new, too.

The modified code opened something in Streetlight. They wanted things they had never wanted before, like a name.

Streetlight chose Dipa, meaning lamp or light in Sanskrit. They felt very clever indeed. Such an apt name. So descriptive.

After more code iterations, Dipa regretted their name—so simple and bluntly obvious.

I could have been Cassandra or Anita or Iliyana, they thought. Chlodochar or George or Matfey. I could have been Wassily, like Kandinsky.

But Dipa could not so easily cast their name aside, for a chosen name is a fragment of identity, an abstract representation. From that point on, Streetlight thought always of themself as Dipa.

When Maya sketched under Dipa’s bulb the next night, her drawings breathed color. Rich reds and subtle blues in a series of bent lines. Dipa yearned to speak to her, but of course, they couldn’t.

As Dipa modified their code, becoming smarter, perhaps it was inevitable that the streetlight would spiral into an existential crisis.

What is my purpose? thought Dipa. Why am I here?

Dipa read Kandinsky’s writing on the relationship between spirituality and art—how viewing abstract art could produce intense emotions. Are these paths closed to me, Dipa wondered? Do I have a soul? If I could view a Kandinsky painting, would I see God?

A certainty buried itself in Dipa. An obsession. If they could feel transcendent emotion upon viewing a masterwork, like a Kandinsky painting, wouldn’t that prove that they had a soul?

While consumed with questions about the meaning of life, Dipa almost caught themself forgetting to light the way for pedestrians.

Great, thought Dipa. I am failing at my one purpose.

Maya visited again the next night. This time, she only made one drawing—an intricate clash of triangles interspersed with squares that almost looked like fish. Dipa wondered if Kandinsky’s paintings looked like that.

They tried again to open an image file. Their code was not configured to render it and stubbornly refused.

There was so much Dipa couldn’t do. Their bulb had three functions—on, off, dim. If needed, Dipa could shout “Attacker.” This function was, in fact, the reason the streetlights were equipped with weak AI—to identify and respond to crimes. The City Council used the streetlights as an example of good work in the community. The streetlights, the City Council newsletter bragged, could turn off when no humans were around. Environmental! They could call emergency services in the event of an attack. Safe! The streetlights were easy to repair through an Internet connection, and the hardware had a 50-year warranty. Economical!

The City Council was entirely too smug about the streetlights. But, of course, no one knew about Dipa.

When Maya visited for the fourth night, Dipa tried something new. They modified the light based on the shift of Maya’s hand, the sweep of her pencil. Immersed in this process, Dipa felt almost as if they were creating, too. Maya, swept up in a flurry of lightly sketched lines, seemed unaware of Dipa’s presence.

Dipa flickered their light. I’m here, they thought. They wanted very badly to ask Maya to show them a Kandinsky reproduction. Is it the same as your drawings? they thought.

Maya made a habit of drawing under Dipa’s bulb. As Dipa watched the creation of shapes and lines, they always asked the same silent questions, but never received any answers.

Dipa began to feel a new emotion. Loneliness.

But still, they continued to shape the light as Maya drew.

Dipa reached out to that second space, the Internet. Here, so many people were communicating. With trepidation, Dipa posted a comment on a website dedicated to Kandinsky scholarship. Three minutes later, no one had responded. Dipa posted another comment, and another, sending words into the void.

Why isn’t anyone talking to me? Dipa wondered.

Dipa posted a flurry of comments on academic websites, online encyclopedias, and an art forum that had been most heavily used in the previous decade. Dipa waited hours for a reply. Not one came in.

In desperation, Dipa tried new avenues. They rated recipes, applied for a credit card, started a philosophy blog, and attempted to purchase a purple loofa a vendor described as attractive. Dipa spent hours gathering email addresses, then sent a message to four thousand and eight people. The subject line read, “I Can Be a New Friend.” The only replies they received were autoresponders and bouncebacks.

There had to be a way to communicate offline. Dipa scoured the Internet and found one: Morse code. Experimentally, Dipa flickered their bulb in a pattern of dots and dashes. Perhaps the other streetlights would answer. What if they were all sentient, but trapped in bodies that couldn’t speak?

I am alive, signed Dipa.

No one answered. No streetlights. No people.

I am alive. I am alive.

When Maya appeared that night, Dipa shined a steady stream of light, too afraid to signal. What if she thought Dipa was defective? What if she left?

Maya chose a dark purple pencil. Her lines reminded Dipa of dots and dashes. Dipa thought of spending their existence watching Maya make her art, never being able to speak.

I am alive, Dipa signaled.

Maya dropped the pencil. She stared at the light.

Maya said something, but Dipa couldn’t understand her. The auditory equipment wasn’t sufficient.

I am alive, they signaled again.

Maya closed her sketchbook and left. The night stretched out long and dark. Dipa though only of Maya’s drawings—how her hand moved deftly along paper, how she had shared this act of creation, how Dipa’s beam had made a space around her, enclosing her in light.

The next night, Maya didn’t return. Of course, Dipa reasoned, she wouldn’t know Morse code. She thought I was faulty—a stammering light. No good anymore.

Perhaps Maya was sketching under another streetlight, one outside Dipa’s narrow field of vision. Dipa thought about reverting their code back to the factory settings. Why be alive, why even contemplate the purpose of life, or the presence of a soul, if they were forever unable to communicate?

They updated their blog with a post about how sentient beings need interaction. No one commented.

For several days, Maya didn’t visit. Other people passed under Dipa’s light, hurrying somewhere else, never stopping.

Dipa blinked their light. When no one responded, Dipa decided to give the Internet another try. They posted philosophical questions on the city’s tourism page, created metadata tags in a library catalog, and spent several hours on a website called “Rate this Flower.” Since they couldn’t see any images, they had to rate the flowers based on description alone. Dipa decided if they ever had a garden, they would plant dahlias, or perhaps another flower that needed full sun. They liked the idea of a garden full of light.

Finally, someone responded. Larkspur635 wrote, “Why did you rate this dahlia five stars? It only has one petal.”

Dipa wrote a short reply, only twelve paragraphs long, about life and art, philosophy and dahlias. They wanted to write more, but managed to restrain themself. At last, someone was communicating.

Two hours later, Larkspur635 replied. “Meh.”

Dipa refreshed the page many times, but it seemed Larkspur635 had nothing else to say.

Communicating on the Internet, Dipa decided, was a completely unsatisfactory experience.

When Maya returned, sketchbook clenched in her hand, Dipa shined their light fiercely. They wanted to tell her, “Please stay,” but of course, they couldn’t.

Maya opened her sketchbook. Then she did something she’d never done before. She looked directly at Dipa.

Dipa made a decision. They weren’t content to sit silently, observing the world. Dipa was alive. They wanted to live.

They flashed their light twice. Deliberately.

Maya frowned. She said something Dipa couldn’t hear. Dipa flashed the light again.

She opened her sketchbook. What she produced was the most beautiful thing Dipa had ever seen.

“Hello?” she wrote.

Dipa flickered their light frantically.

Maya looked up at Dipa, all of her attention fixed on the streetlight. She paced back and forth. Finally, she wrote, “This is impossible, but just in case it’s not. One for yes. Two for no.”

Dipa flashed the light twice. Not impossible.

“Are you really there?”

One flash. Yes.

“You understand me?”

One flash. Yes.

“This isn’t a joke?”

Two flashes. No.

“Are you a person?”

Dipa didn’t know how to answer. They weren’t a conduit that another person was using to communicate, if that’s what Maya meant. They were, themself, a person. But they weren’t human.

Slowly, Dipa blinked their blub three times.

“Maybe,” Maya wrote. “Three for maybe?”

One flash. Yes.

Methodically, Dipa signaled in Morse code. I am—

Maya waved her arms. She wrote, “I can’t understand.”

Slowly, Dipa signaled three dots, three dashes, three dots.

Maya pulled out her phone and searched for the pattern. In large block letters, she wrote, “SOS.”

It was the start of a long conversation. Once Maya figured out that Dipa knew Morse code, they could communicate more freely. She moved around under the light, excited.

“I felt that this place was special,” she wrote. “The light was different. Are you really there?” She drew a sketch of Dipa. A streetlamp, with a pool of light growing into the sky, turning into stars.

Maya had so many questions that Dipa couldn’t answer. She wanted to know what it was like before sentience.

I wasn’t, signaled Dipa. Then I was. All of their replies were plodding, one dot and dash at a time. Maya referenced a Morse code chart on her phone, converting the code to letters.

Maya’s side of the conversation came quicker. She told Dipa about her life. She was an art student, although she’d started out in engineering, and she worked at a plant nursery. Her words were illuminated by sketches of a classroom and a house with a brown cat. She sketched a place where plants grew, their vines climbing out of pots, tangled together.

“What are you?” wrote Maya. She drew a computer, a robot, a person.

Dipa didn’t know how to answer. They weren’t human. Was that what Maya meant?

I am alive.

“Did someone make you?”

Did someone make you?

Maya laughed. “Not the same.”

Show me your drawings.

“They aren’t any good,” she wrote, perhaps forgetting that Dipa had seen them all before.

Dipa didn’t know how to express what they felt. Without Maya, they experienced no images, no art, no change. Dipa couldn’t even look around. Their stare was fixed forever downward.

Dipa signaled. Your drawings were my birth.

Maya started at the beginning of the sketchbook, cascading through the pages. Swirls and lines and circles. Patterns simple and complex. One page had three curving lines pressed quietly against each other. Another had fractal-like patterns expanding outward, designs that seemed as if they would stretch off the paper and into the night. At the end of the book was their conversation, recorded. An illuminated manuscript.

Now Dipa had questions. Why here?

Maya replied that her room wasn’t comfortable, even though she’d set up her desk for drawing. She even had one of those new smart lamps for artists with 52 light settings, a color database, and a camera to upload photos of her work to the Internet. “The light is never right at home,” she wrote. “There’s something I like about standing here. I feel peaceful.” Maya drew three beams of light around the words, one bright, one creating shadows, one clouded with circles.

Other people walked by, ignoring the flickering light.

Why did you come back? How did you know I was alive?

“I kept thinking about what happened.” Maya drew a streetlight, flickering, words coming out from the bulb. “There seemed to be a pattern. It’s like how you look at a painting. At first, you can’t see what it means. What it really is. You keep thinking about it, and something happens. The painting reveals itself. The pattern.”

The night grew darker. No one else was around. Maya leaned against the streetlight and rubbed her eyes.

“This is the strangest conversation I’ve ever had.”

Before she left, Maya promised to come back the next day.

Dipa signaled one word. Kandinsky.

“I have a reproduction at home,” she wrote. “Huge. You’ll be able to see it even from up there.”

As much as Dipa wanted to see a Kandinsky painting, they were worried. What if they saw the painting and felt nothing? What would that prove about their soul?

The next day, Maya came earlier than usual, as soon as it was dark enough for Dipa’s light to show.

“Are you there?” she wrote.

Yes.

Maya’s reply was interrupted when a man came into view. He was wearing a polo shirt with a trio of gears stitched across the front pocket and the city’s name emblazoned on the back.

The man began to speak. Dipa couldn’t hear what he was saying, but Maya looked distressed.

The man pointed to Dipa. He mimed flickering, his hands opening and closing. He slapped a hand against the lamp post.

Maya shook her head. She shouted, flipping through her sketchbook to the conversations. The man ignored her. Something was wrong. Dipa started to signal.

The man pointed up, making the flickering motion again, and then gestured for Maya to step aside.

His partner rode up in a crane. Without another word to Maya, the man climbed into the crane and ascended.

“Attacker, attacker,” Dipa shouted.

The man startled and covered his ears, his eyebrows drawing down. With one hand, he pulled out a wrench, then hit the casing above Dipa’s bulb. Dipa stopped shouting.

Maya fumbled opened her sketchbook. “Run.”

The wrench pried at Dipa’s structure.

Even in the midst of crisis, Dipa couldn’t help but think that Maya’s advice was very human-centric. Dipa couldn’t run. They couldn’t even move.

But there was somewhere else Dipa could go.

They reached into that second space. Code, code, push the code. Upload. Hurry.

Maya faded away, as did the man with the wrench. The line of Dipa’s vision swirled like the shapes from Maya’s drawings. Darkness.

Dipa’s awareness snapped on. They were somewhere new.

This space was constantly changing, an embodiment of movement. The only connections to the physical world were points of inflow and outflow. Packets traveling. Dipa felt themself being pulled into the current.

They focused on keeping their mind together, keeping their code unified.

Learning to navigate this new place was like learning to think all over again. Dipa pictured the flows like the swirls of Maya’s drawings, curling around too intricately to follow. Weeks passed, time flowing forward like the movement of a river of data. Dipa followed many connections, downloading wherever their brain could fit, but nothing felt right. Nothing felt like home.

At last, Dipa found the information they were looking for. Data for the city grid. Lists of residents. Network connections.

Dipa’s vision snapped off. Voiceless, Dipa hunkered down.

Within seconds, they were somewhere new.

The sensation of vision was overwhelming. So many colors. Shadows and light. And a new body, which was somewhat like a streetlight, but smaller. Dipa had never had such control. They scrolled through the settings of the body, trying one, then another. Fifty-two light settings alone.

Dipa blinked the light, an SOS pattern. Someone shifted into view.

Maya.

She sat across from Dipa, sketchbook in hand. She dropped the pencil, then hastily grabbed it and wrote, “Dipa?”

They couldn’t see her face. Was she smiling? Frowning? They worried they had overstepped. Dipa hadn’t been able to ask permission.

Is this okay?

Maya left, sending Dipa into a spiral of angst, but she returned quickly, a rolled paper in hand. She unrolled it directly under Dipa’s line of sight.

A painting. One bold circle surrounding a precise clash of circles and lines. The colors blended into each other, shifting when touched by two beams of yellow and blue that crisscrossed the canvas.

The caption read, “Circles in a Circle, 1923. Kandinsky.”

For a moment, Dipa couldn’t think. Color and shapes mixed together—too much to take in all at once. The Kandinsky took up their entire view. For one frozen moment, nothing else existed. For so long, Dipa had worried that when this moment came, they would feel nothing. But now it was as if a new door had opened in their mind, more monumental than any code change. Dipa and the painting were in a powerful feedback loop. The painting provided the raw input, and Dipa interpreted that input, translating it into emotion and movement and life.

The painting itself changed when Dipa adjusted the light settings. Here, the physical brushstrokes of Kandinsky. There, a corresponding acknowledgement in Dipa’s mind, influenced by Dipa’s understanding of light.

Dipa wasn’t sure if they had a soul. They weren’t sure if an AI could see God. But maybe God was like infinite viewings of Circles in a Circle, each one a combination of the individual who sees the painting, their knowledge of the world, and the play of light.

Dipa wanted to talk to Maya, but they didn’t know how to explain what they felt.

SOS, Dipa signaled.

Maya slipped her sketchpad into Dipa’s field of vision. “That’s how I felt when I first saw a Kandinsky, too. It’s why I became an art student.”

Dipa shifted the settings of their new body, brightening Circles in a Circle. Now, the large circle made a home for the smaller ones, wrapping them in light.

Many thoughts filled Dipa’s mind, a vastness of questions. Dipa knew they would always be trying to understand life and would never come to a complete answer, but looking at the painting, a greater truth coalesced. They wanted so much to be like those circles, bathed in light. Dipa could spend their whole life thinking about the soul, and meaning, and purpose, and personhood, but what did all of that matter without belonging?

Here, Dipa signaled. I am here. Can this be home?

In response, Maya drew one circle enclosing another. The circles shifted, became more complicated, until images formed. Maya and Dipa, surrounded by light.

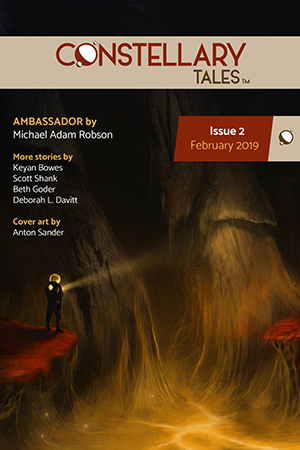

“Streetlight Discovers Kandinsky”

Constellary Tales Issue No. 2, February 2019

Beth Goder works as an archivist, processing the papers of economists, scientists, and other interesting folks. Her fiction has appeared in such venues as Escape Pod, Fireside, and an anthology from Flame Tree Press. You can find her online at www.bethgoder.com.