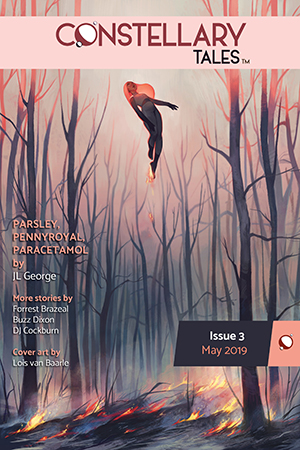

“Under the Hat”

By Forrest Brazeal

Dwayne’s reflection in the flyspecked bathroom mirror at the Economy Inn seemed to flicker before his eyes like a black-and-white filmstrip reaching the end of the reel. His broadcloth suit was worn now from years of use in classrooms and small-town lecture halls—appropriately so; the Great Emancipator often received criticism for his shabby appearance. His diamond-point bow tie perched scraggly and slightly cockeyed just under his chin. But the silk stovepipe hat with the tiny buckle on the band still maintained its regal insouciance. It traveled with him in its own hatbox and had never been crushed in 21 years.

He frowned, squinting in the dim light, and inspected his beard. He was proud that he had always worn his own hair to play Lincoln. But his temples and chin now tufted noticeably gray. Soon he would either have to dye the beard or learn a new character—Mark Twain, perhaps, or Albert Einstein.

Or, more likely, his career was already over. He winced as the sound of the TV in the bedroom cut into his thoughts. That hated voice, faux-folksy, unnaturally deep. “Yes, my fellow Americans. If elected, I promise that government in this country will once more be of the people, by the people, and for the people. And we will not perish from the earth.”

His phone rang, and Dwayne, turning off the TV in the middle of the crowd’s applause, answered without checking the caller. “Dwayne Potoczak.”

“Hey! Big D! Glad I caught you.”

Dwayne scowled again. Long ago, he and Reed Barton had studied history together at William and Mary. Now Reed had sold his soul to the Lincoln campaign as a technical advisor. Nice work, if you could live with yourself. “The answer’s still no, Reed.”

Reed paid no attention. “Did you see the highlights from last night’s rally? Twenty thousand people cheering the jumbotron in the Tigerdome.”

“I must have missed it.”

“I think we’ve finally nailed the mannerisms,” Reed continued. “I mean, of course you can never really know, but…”

“You can know when you get it wrong,” Dwayne interrupted, unable to keep himself from rising to the bait. “And it’s all wrong. The voice is too deep. The accent is Virginia, not Kentucky. And he—it—it weaves too much on the screen. Lincoln planted during his speeches. They said you could put a silver dollar between his feet and he’d never touch it.”

Reed’s voice became ingratiating. “I wish you’d give us just a day at the campaign headquarters. You’re the best Lincoln impersonator still working. Let us train the machine learning algorithm with some of your signature moves. I think it will make a huge difference.”

“You can’t afford me,” said Dwayne.

“We’d pay scale.” Reed lowered his voice slightly. “And listen, this is between you and me, but if we get elected, I think I can promise you a McCafferty fellowship. Federal funds. You’d never have to recite the Gettysburg Address for a room full of bored third graders again.”

“I’m late for work, Reed.” Dwayne dropped his phone onto the bed with the man’s voice still quacking away.

He arrived at Sun Creek Primary School just after 10:30 and waited in the lobby for the call to visit Mrs. Miller’s fourth-grade class, holding his body stiffly on a metal folding chair. He wore 3-inch platform shoes to bring his height up to Lincoln’s, and his knees towered in the air like split rails.

A child holding a hall pass wandered up to him with a deeply critical stare. “Are you Abraham Lincoln?”

“That’s right.” He bent down and offered a kindly smile, crinkling his eyes at the corners.

The child shook her head. “My mommy and daddy are voting for Washington.”

Dwayne grimaced into his beard. The ersatz Lincoln was bad enough, but whoever was behind the walleyed cartoon of George Washington on the opposing ticket ought to be shot. “Ah yes, the father of our country,” he said, checking himself as the principal appeared in the lobby.

“Back to class,” she said to the child. Then, to Dwayne, “Sorry to keep you waiting.”

“No trouble, madam.” Dwayne unfolded himself from the chair like a carpenter’s ruler, pressing her hand with an elbow-heavy pump action. “I’m put in mind of a story…”

She shook her head. “Not now.” Looking around to make sure the child was gone, she continued in a low voice, “I’m sorry, but I don’t think we’re going to be able to do this today.”

“I beg your pardon?”

“Mrs. Miller… she’s worried that it may confuse the children.”

“Confuse them?” Dwayne gaped at her, dropping his rolling Kentucky drawl. “I’ll tell you what’s confusing. A computer-animated slushpile of linear algebra running for president of the United States, that’s what they should be confused about.”

“Well, we try to keep politics out of the classroom.” The principal waved her hand vaguely.

“Lincoln’s not politics. He’s history.” Dwayne heard his voice rising. “And we set this date months ago.”

“I’m sorry,” she said again, taking his arm and propelling him gently yet irresistibly toward the door. “Maybe sometime later… after the election is over… ”

In his car, an elderly Camry with a fritzy A/C compressor, he flipped through a brown-vinyl date planner. One tentative gig in Muncie on the twenty-third, barely enough to cover his gas even if he made it out there. After that—nothing. Why hire a reenactor when you can get the so-called genuine article on TV every night of the week?

He put the silk hat carefully in its box on the front passenger seat. He sat parked in the school’s carpool lane for a long time, staring out the windshield while the late morning sun heated the Camry into a stale-smelling convection oven.

When he finally called Reed, his beard left moist sweat on the phone. “Are you really serious about the McCafferty fellowship?”

“Sure I am.” Reed was eating something sticky on the other end of the line. He smacked his lips with gusto. “This is a shoo-in, Big D. Easiest payday of your life.”

“I’ll give you one afternoon,” said Dwayne. “That’s all.”

“Totally understood. And Dwayne…”

“What?”

“Keep this under your hat, okay?”

Dwayne hung up on the sound of Reed’s sticky giggles.

He dressed carefully the next day, unzipping a black garment bag he’d last opened at the Appomattox sesquicentennial. The shawl-collared four-pocket waistcoat and front-pocket trousers. The double-breasted frock coat with the embroidered silk lining: an eagle clutching the words “One Country, One Destiny” on a scroll-turned banner in its beak. Around his hat he carefully fitted a 3-inch mourning band of stiff black grosgrain. It was, in every possible way except the bloodstains, an exact replica of the suit President Lincoln had worn to Ford’s Theater on the evening of April 14, 1865. The trousers, frock coat, and waistcoat were all wool, and he began to sweat before he even left his motel room.

“Oh, you don’t need to be wearing all that,” said Reed, who let him into the Lincoln campaign headquarters by a rear door.

“Yes, I do,” said Dwayne.

The campaign headquarters was a long, low building just outside Annapolis, surrounded by chain-link fences. It looked very much like a corporate datacenter, which was exactly what it was. The two men walked for a long time through white fan-cooled corridors that reverberated with every clop, clop of Dwayne’s platform shoes.

“It’s really quite remarkable, when you think about it.” Reed sounded eager to fill the vacuum of silence between them. “We’re past the age of political scandals. I mean, even Honest Abe had his skeletons, or would have if the modern media had been around to dig them out of his closet. But we’re not running Lincoln in this election. We’re running the idea of Lincoln. A symbol. Flawlessly on-brand for us.”

“Nice that the symbol just happens to agree with every plank of your party platform,” grumbled Dwayne.

Reed dipped his eyes modestly. “Well, we feel that the original Lincoln would have been quite enthusiastic about our—”

“Save it for the press.”

Reed tried again. “People used to worry about AI enslaving mankind. But you can’t exactly picture Abraham Lincoln as a despotic overlord, now can you?”

Dwayne made no reply.

They reached a thick unmarked door, and Reed tapped a code into a keypad, allowing them into a low-ceiled open office space. “Welcome to the land of Lincoln!” he exclaimed with an airy wave of his arm.

Chest-high cubicles sectioned the room, most staffed by young people in Lincoln campaign polo shirts. Software design diagrams and scraps of code littered whiteboards and spilled out of wastebaskets. Fat racks of servers whirred in a corner. Nobody so much as glanced at Dwayne.

“Hey, Naral.” Reed jostled the shoulder of a programmer near the door. “This is my old friend Dwayne Potoczak. He’s a Lincoln buff.”

“A professional performance artist and award-winning historical reenactor,” Dwayne mumbled.

“Cool,” said Naral without looking up.

Reed grabbed his monitor and twisted it in Dwayne’s direction. “Show him the new beta.”

Naral made an annoyed grunting noise. He tapped his keyboard. Out of the depths of his screen swam an image that moved and smiled, something with fathomless dark eyes that looked right across the uncanny valley and pulled Dwayne in headfirst after them. “Well, I’ll be a circuit-riding sawhorse trader,” said the deep voice synthesized from untold convolutions of speech-selecting neural networks. “It’s my twin.”

Dwayne looked at himself in alarm, then at Reed. “It sees me.”

Reed chuckled. “Cool, right? Broadcast is great, but we want to send this model on a personal tour of every swing voter’s computer. No time and space limitations! We can do a hundred thousand meet-and-greets at once.”

“That puts me in mind of a story,” said the artificial Lincoln on the screen. It leaned forward on one elbow and Dwayne was forced to admire the detail of a tiny bit of dirt under its fingernails, as if it had just come from a barn raising. “Two men were chasing a pig through the woods. The first one said, ‘Why isn’t this pig a bear?’ And then both of them expressed their views on the slavery question with a healthy discussion that was prior to, and independent of, the bear and the pig combined.”

Naral made another irritated sound and pulled the screen out of their reach. “Still training the predictive speech on this model,” he said.

Dwayne drew a shaky breath. “Let’s get started.”

They took him to a side room draped in green fabric. Interns clipped tiny white sensors on his face and body. They took his hat away and put it on a messy table. They asked him to walk from here to there, gesture this way and that, read excerpts from the news of the world in his rendition of Lincoln’s voice. Dwayne did his best, but his efforts were flat and artless. He couldn’t conceive of how Lincoln would even pronounce the word ‘cybercrime’ or ‘Kyrgyzstan’. The whole effort was a parody of itself, a kind of cultural self-consumption.

This is what happens, he thought—you start by remaking movies and rebooting TV shows, then you bring back fashions and policies and moral attitudes, and before you know it you’re recycling entire presidencies. Why face the future when you can have the past again, packaged in an appealing layer of hindsight and tied up with a bow of nostalgia? His voice cracked as he attempted to fit Lincoln’s high, precise diction around a magazine piece about sunbathing sister wives in Orlando.

Someone looked up from a laptop in the back of the room and leaned in to whisper to Reed. The harsh tones floated easily to Dwayne. “I thought you said this guy was good.”

Reed shook his head. He crossed the room to Dwayne and stood on tiptoe to put an arm around his coat-hanger shoulders. “Hey, Big D. You okay?”

“Yeah. Sure.”

“Listen, why don’t you do one of your bits? Gettysburg, or the Second Inaugural? It won’t hurt us to get some more reference data.”

“They aren’t bits,” said Dwayne.

“I’m just trying to help you.” For the first time, Reed sounded impatient. “Do you want to do this or not?”

Dwayne sighed. “Just give me a minute.”

He stood silently in the middle of the room while Reed retreated, imagining himself in the various scenes of Lincoln’s life, as though his mind could composite its own images on the green screens around him. The Second Inaugural Address was his best and favorite Lincoln speech, but it didn’t seem to fit this moment. Neither did Gettysburg, or Cooper Union, or most of his repertoire.

At last he began to recite, slowly at first and in a hushed tone, the words of the Lyceum Address, an early text from the Springfield days. “As a subject for the remarks of the evening, the perpetuation of our political institutions is selected…”

He slipped comfortably into the flow of the angular, vivid prose, as familiar to him as the bug-splattered windshield of his Camry. He knew Lincoln and had achieved a platonic intimacy with him through years spent on the road together. He understood as well as any historian the man’s keen mind, his ability to make the complex simple, his wry political calculations, his crippling depression. He’d often compared himself to Lincoln’s old roommate Joshua Speed, sharing a bed with greatness over the general store.

I do not mean to say that the scenes of the revolution are now or ever will be entirely forgotten; but that like everything else, they must fade upon the memory of the world, and grow more and more dim by the lapse of time. But what did the AI Lincoln understand of time and memory? It was a decision-making machine with a synthetic personality, an avatar with yammering nothingness in its eyes, perpetually trapped behind a computer screen like the victim of some programmer’s curse. What, from its multilayered training data, could it possibly know of the man whose legacy its creators exploited?

What could anyone know, really? History grows dim, and every layer of interpretation slathered on top puts the original further out of reach.

His voice quavered as he reached Lincoln’s conclusion. Passion has helped us; but can do so no more. It will in future be our enemy. Reason, cold, calculating, unimpassioned reason, must furnish all the materials for our future support and defense. Let those materials be molded into general intelligence… After all, what made him, Dwayne Potoczak, different from the synthetic Lincoln in the server rack? Both of them scavenged the past for legitimacy. Both were, essentially, interlopers in a reality they’d never experienced. Here was the difference: The AI was going places. Dwayne was not.

He stopped speaking abruptly, not bothering with Lincoln’s final rhetorical flourish about the gates of hell. “I think I’m done.”

“Good stuff, good stuff,” mumbled one of the programmers.

“Yeah, we can layer some of this in,” added another, pointing to something on a monitor Dwayne couldn’t see. “I like the, uh, the pathos. That’s very Abe, I think.”

Reed smiled broadly. “How cool is this,” he said. “There will be a little piece of you in the next president of the United States.”

When he got back to his motel room, Dwayne stepped out of his Ford’s Theater suit—a soggy mass of wool by now—and left it in a heap on the floor. He held the stovepipe hat indecisively for a minute, feeling a powerful urge to stomp on it. At last he shoved the hat into a dark corner of the closet. Then he lay face down on the smoky-smelling bedspread and did not sleep.

Abraham Lincoln 2.0 swept the electoral college. In its final televised debate, it reduced George Washington to a stuttering mess of non sequiturs, revealing that much of the opposition’s fabled deep learning technology was just cleverly-staged string matching.

Dwayne could not bring himself to watch either the debate or the election returns. For the first time in his adult life, he did not vote. The scale pay from his afternoon at the headquarters had run out, and he got a job through a temp agency doing data entry for subprime auto loans. He continued to live in the motel, which was cheaper than the effort required to find an apartment.

A couple months after the inauguration—where alt-Lincoln held its digital hand on a CGI Bible—Dwayne swallowed his pride and called Reed.

Reed was smacking his lips on something as usual. “Hey Big D! Guess who’s gonna be the new technology czar?”

“That’s great, Reed. I’m happy for you. Listen, I was just wondering about the McCafferty thing… if there was any update…”

“Oh, right.” Reed swallowed his bite and was silent for a minute. “Uh, you didn’t hear about that?”

“How would I have heard about it? You haven’t called me.”

“I meant on the news.”

“I don’t watch the news.”

“Oh.” Reed sounded even more uncomfortable. “Uh. Well, the McCafferty program has actually been defunded. Executive order.”

“What do you mean, defunded? Whose order?” Dwayne paused a second. “The AI’s?”

“It’s not just McCafferty,” Reed hastened to add. “NEA, Met Council. Pretty much all federal funding for the dramatic arts.”

“That wasn’t part of the party platform.”

“No. No, it wasn’t,” Reed agreed. “Uh, we aren’t exactly sure how it happened, but the neural network that we trained on Lincoln’s life—it seems to have learned some self-preservation instincts about theaters and stage plays. Has a bit of a paranoia, I guess you could say.”

“That is utterly ridiculous.”

“We’ve got our engineers working on it. I can’t promise anything, but maybe after the midterms we can roll out an update…”

“Sure.” Dwayne sagged onto the bed.

Reed adopted a cheer-up tone. “But think of it this way, Big D. You had the opportunity to be part of something so much bigger than any of us. Your voice, your movements, your soul, are a vital part of the training set for the first algorithm ever elected to major political office. That’s the greatest reward of all. Trust me.”

“Oh, Reed,” said Dwayne. “I never trusted you.”

He sorted through detritus in the back of the closet. The stovepipe hat still sat where he had left it, a little scuffed but otherwise unharmed. He turned it over and fumbled in the lining. Eight-and-a-half inches tall, the perfect size for a rolled-up sheet of copy paper. Lincoln had kept important documents in his hat, after all.

He pulled out a thick sheaf of papers and spread them on the bed. Architecture diagrams, schematics, swatches of code. He’d grabbed things at random from the headquarters throughout that afternoon, prioritizing stealth over careful examination. It didn’t matter. The grad students who staffed the campaign were predictably careless. He wasn’t technically astute enough to be sure of exactly what he had, but he suspected that in the right hands it was enough to reverse-engineer the Lincoln AI. Maybe even enough to hack it. He picked out a particularly interesting design document and scanned it into his computer.

The opposition party’s website had a splash page with a picture of their pathetic George Washington bot waving to supporters through a giant TV screen. (FIRST IN THE HEARTS OF OUR COUNTRYMEN, read the caption.) More importantly, they had a secure contact form. He uploaded the document with the accompanying message: More where this came from. Make me an offer. Let’s delete the president. He thought for a moment, then signed the note Yours in conspiracy, J.W. Booth.

He went to the bathroom, ran a basin of hot water, and got out a straight razor. He had let his beard grow out full in the past months, and he attacked it now like an explorer clearing tangled wilderness, removing everything except a thin mustache on the upper lip. The face that emerged in the mirror was younger, bolder, and remarkably devilish.

After all, the Lincoln AI wasn’t so smart. If it really wanted to avoid its predecessor’s fate, it wouldn’t have adopted the one policy guaranteed to create a bunch of frustrated actors. Dwayne began to smile, tapping his fingers on the sink, and then threw back his head and chuckled delightedly. “Sic semper tyrannis,” he said, and shook his dark hair over his forehead with an assassin’s raffish grin.

“Under the Hat”

Constellary Tales Issue No. 3, May 2019

Forrest Brazeal is a software engineer, writer, and cartoonist based in Virginia. His stories have appeared or are forthcoming in numerous publications, including Daily Science Fiction, Diabolical Plots, StarShipSofa, and Abyss & Apex.