“Memorial Park”

By Stewart C Baker

It takes a special kind of self-loathing to document a whole life’s worth of mistakes, to cross-reference half-heard wishes with forgotten birthdays and work commitments with canceled vacations. But that is what Cordelia has done for the past six months while her daughter, Julie, lies in the hospital bed, quietly dying.

“She’ll probably pass tonight,” the doctor says in a hushed conference outside the room.

Cordelia does not cry. “Thank you,” she says. “For everything you’ve done.”

Back in the room, Julie is awake, her eyes heavy with morphine.

“What did he say?”

“It’s nothing, Sweetie,” Cordelia tells her, stroking one paper-thin hand. “How about a chocolate?” Feeling the total useless futility of the gesture even as she speaks. Hating herself even for making it.

But Julie just smiles. “Thanks, Mom.”

“I’m just going to the bathroom,” Cordelia says, as her daughter puts the candy in her mouth and closes her eyes again. “I’ll be back before you know it.”

Door closed, she sits on the unopened toilet seat and takes deep breaths until the lump in her throat recedes.

She will not cry. She will not.

“It’s amazing, the advances they’ve made in technology,” the grief counselor says to Cordelia. “You can hardly tell the animals are constructs.”

It’s unnatural, Cordelia thinks as she flips through the glossy brochure. A deer, ears flicked back in surprise, seen through bushy summer undergrowth; a hummingbird mid-flight, wings frozen. Each with a tag on its body displaying the deceased’s information. Abhorrent. Bizarre. But she bites back the words.

“It just feels so selfish, keeping her here,” she says instead, barely managing to stop her voice from breaking on the final word. “I don’t want her to be gone, but…”

“A lot of people say that. And it’s important to realize that the construct won’t be your daughter. It won’t bring her back.”

“I see,” Cordelia says, grasping for the words. “So it’s… just a fancy grave?”

“Yes and no. While it’s not your daughter, the construct’s actions are informed by her biosignature, taken from brain scans before cremation. Your daughter will be at rest, but some tiny remainder of her—some small piece of her fondest hopes and dreams—will live on inside it.

“Our studies show the experience to be more emotionally satisfying than a computerized reconstruction, which invariably gets minor details wrong and stifles the grieving process. Constructs are a healthier path. They help people realize it’s time to let go.”

Cordelia remembers a birthday two or three years past when she’d promised Julie a stuffed unicorn—some kind of super-popular fad she’d never bothered learning more about. Despite her promise, she had of course forgotten, and hadn’t remembered until weeks after the day, when she’d called home from work to say sorry.

It’s okay, Mom, Julie had said. I like the gifts you got me.

Cordelia had felt guilty, but hadn’t done anything about it. Like always. She closes the brochure and takes a long, slow breath. “Any creature, you said?”

It is bitterly cold in the memorial park, the fir trees covered with a dusting of snow. The deployment deck is deserted, with none of the smiling, laughing families from the brochure. No crowds, no clutter, no noise. Cordelia leans her elbows against its rough wooden railings and thinks upon birthday presents and funerals, upon promises and hospital beds. One last time, she counts her many mistakes.

When she is ready, she keys the code the tech crew gave her into the deck’s control panel. There is a deep, low rumble which she feels more than hears, and the unicorn leaps out into the clearing below. Its haunches are a shaggy white cut through with starlight, its tail a silvery magnificence. Its mane shimmers with a shade of blue so light it seems translucent.

A magnificent beast, just like the ones Cordelia herself dreamed about as a little girl, running fantasy after fantasy through her mind. She wonders how it matches Julie’s own imaginings, and she hopes it is close.

The unicorn takes a few tentative steps forward, then lowers its head and nuzzles at the frosted grass.

For a moment, all is silent stillness, and Cordelia dares not even breathe. Already she can feel the nagging beginnings of guilt: What if the construct does not look back? What if something has gone wrong with the procedure somehow and her daughter’s consciousness is really in there, disoriented and forever alone? And even if everything goes right, what does it matter? Her daughter is dead, and this won’t solve that. Nothing will. What if this has only been another mistake?

Then the construct shakes its mane. Against the wintry backdrop, the unicorn with its glimmering fur and pearly horn does not seem even slightly out of place. Steam rises from its nostrils as it lets out a soft whicker and turns its head to looks back at the deployment deck. At Cordelia.

There is nothing in those manufactured eyes of Julie, not a shred of anything human. And yet… As their gazes lock to one another, Cordelia’s breath catches. The moments stretch out until time loses meaning.

Is this communion? Cordelia wonders. Or programming? Part of “the grieving experience”? She leans forward over the railing, and the motion knocks a heap of snow to the ground with a muffled thump. As though the noise has broken some connection, the unicorn bounds away into the forest.

Cordelia stands there on the deck, waiting and watching, until the sky goes crimson behind the silhouetted trees. It is only when the sunset fades and the moon comes out, full and blurry against the stars, that she realizes she is crying.

“Memorial Park”

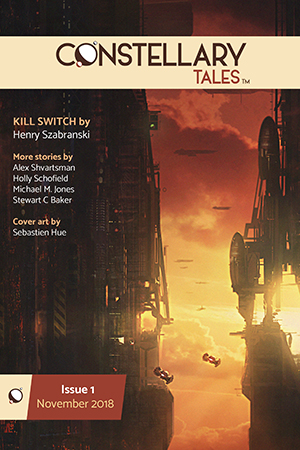

Constellary Tales Issue No. 1, November 2018

Stewart C Baker is an academic librarian, speculative fiction writer and poet, and the editor-in-chief of sub-Q Magazine. His fiction has appeared in Nature, Galaxy’s Edge, and Flash Fiction Online, among other places. Stewart was born in England, has lived in South Carolina, Japan, and California (in that order), and currently resides in Oregon with his family—although if anyone asks, he’ll usually say he’s from the Internet.