“CurioQueens”

By Ephiny Gale

The very first time I play, I am eleven. My parents are collectors and connoisseurs of magical artefacts, although 90 percent of these are completely inert. The latest one, however, is not.

I am, in the strictest terms, Not Allowed to Touch It, but I can’t remember anything I’ve ever wanted more, and my parents have never been very good at following through with punishments. I convince my father to go horse riding and wear him out. I steal the key from the inside of his boot while he is sleeping.

My mother catches me cross-legged on the storeroom table, stroking the most beautiful game board I have ever seen. She says that if I’m going to insist on playing, that she’ll play with me, because the most dangerous way to play is with someone who doesn’t love you.

The board is solid and three-dimensional. It looks rectangular from above, but from the side it resembles a stretched-out witch’s hat with a flattened tip. Along the top, the name CURIOQUEENS is engraved in large capital letters, and underneath that: A game of trust. The entire board is made from expensive crystal, opaque in the middle and transparent on the “brim” where the cards are placed. “So the board can read what cards you’ve played,” says my mother.

She explains the rules as follows:

1. You will receive 10 cards and must play five.

2. Most of the 300 possible cards are good cards, with positive or neutral effects like “Never have the flu again,” or “your hair turns permanently blue.” However, about 20 percent of the pack are bad cards that will cause the players harm.

3. Some of the cards will affect you, some will affect your opponent, and some can do either depending on which way you orient them on the board.

4. Approximately a third of the cards are whisper cards, which means that you can’t tell your opponent what they are or the game will break your fingers and sew your lips shut.

5. Looking at the cards outside of playing the game, or not completing a game once it has begun, will be punished.

I stare at my mother then, and she says, “So you can’t relax your arm and let me see your hand, like you sometimes do by accident. Do you still want to play?”

I do, so she reaches out and pulls a hair from the back of my neck, which is tradition, and ties it around a small post next to the CURIOQUEENS letters. Once I’ve done the same with her hair on the opposite post, there is a barely perceptible humming, and then the game serves us each 10 cards from the slots that open halfway up the board.

The cards are all backed with gold foil, and I pick them up reverently.

My first task is to read all the cards carefully and sort the good cards from the bad cards. I have three of the bad cards—I move them to the back of my fan. This is easy!

“It might be easy today,” says mother, “but it wouldn’t be easy if you had more than five of the bad cards.”

“That’s unlikely, though,” I say, puzzling over whether I would rather be 7 percent more beautiful or 7 percent better at math.

“Unlikely, but far from impossible.”

I start laying my chosen cards face-down in their crystal slots, making extra sure that my mother can’t see.

My mother is holding up one card in particular. “Would you like to meet your soulmate in five years under an oak tree?”

At sunrise on the same date, exactly five years later, I hurry down to the oak tree a kilometer or two from the house. I am wearing one of my best dresses, lilac with embroidered white roses, and mother has curled the ends of my hair. I have a heavy picnic basket to share with my future husband when he arrives.

I watch the morning stream of people and horses, women with baskets across their shoulders and boys flicking the sleep crusts from their eyes. I pay precise attention to all the young gentlemen that pass. None of them pause to speak with me. Some of them glance at my dress, or smile; I wonder if that counts as us meeting.

By lunchtime I am nestled between the roots of the tree, chewing on a cracker. Surely my soulmate will not miss a few biscuits.

And then it is sunset, and many of the people I saw in the morning are coming back the way they came. I try to keep myself pretty, my skirts arranged neatly around my knees and my eyes pinned to the road. There are still plenty of hours left to meet my soulmate, and the game has never been wrong before.

A girl about my age asks why I’ve been fixed to the same spot all day. I offer her a truthful explanation, but I don’t dare pry my eyes away from the men on the road. She returns after dark with a blanket and a flask of hot cocoa. She keeps me patient company into the night.

We wake up together the next day, underneath the woolen blanket, propped against each other and the tree trunk. I see her face properly for the first time and feel the universe slightly realign.

“Oh,” I say.

And she has the most radiant smile.

The girl’s name is Mina, and we marry during my twentieth year. We braid orchid flowers into each other’s hair and jump from ropes into lakes and keep no secrets from each other, save the ones from CurioQueens that keep safe our mouths and hands.

We only play the game twice, once during our engagement and once not long after our wedding (the first time, I gain an advantage on creating good first impressions; the second time I lose both my little toes). Mother managed to imbue me with a healthy respect for the game’s dangers, but it follows me around. It seems that “my fondest medium-sized wish” from when I was eleven was to be able to play CurioQueens whenever I liked, and the game manifests this by appearing within reaching distance whenever I wake, regardless of where I may have left it the night before. In my jokes my board is my faithful hound, and on occasion I tap it gently on its title like a pet.

Until the day that Mina never comes home.

She is found ten minutes’ walk from her flower shop, crushed by a bolting horse, daffodils and carnations flattened into her bruised skin like decoupage. When I finally see her, my own skin pales until it almost matches her deathly white.

I check the date in my diary with shaking hands. It is not long past our second wedding anniversary, and thus well within the realms of possibility.

From previous experience, I know there is a whisper card in the CurioQueens deck marked with You will die two years from today, and that may be pointed towards either of the players. I am struck with the deep and terrible knowledge of something I can never prove, and in that moment I both fervently love and hate my Mina with equal measure.

My mother and I take honeycomb tea in her upstairs drawing room. I am still in my funeral clothes, with the veil pinned back so that it does not drip into my teacup.

“But what would the rest of her hand have been,” I say, “to make her choose that card.”

My mother is chopping an éclair into several equal sections with a fork. “You’ll never know that, Victoria. The important thing is that she protected you. You made the right decision, playing with someone who loved you more than she loved herself.”

My eyes are defocusing. I place my own half-eaten macaron back on the coffee table.

Her cutlery clinks on the china. “You recall how I told you what the CurioQueens games were made for?”

“Perhaps.” I have a vague memory of her telling me this years ago, back before I’d even met Mina. “They were presents to foreign royals, their courts and other influential people. For diplomacy.”

“It was presented as diplomacy, certainly.” Out of the corner of one eye, I see my mother spear a section of éclair with her miniature fork. “But that’s not the generally accepted understanding now, and certainly not the one that your father and I subscribe to. Those games are weapons.”

She waits for me to properly hold her gaze before she continues: “Please don’t play again.”

I trade my widow’s skirts for saddle pants. I pack my horse light. I do not bring the CurioQueens board, though of course it will follow me anywhere. I tell myself I don’t have a destination in mind, that I simply wish to get away. And then my first morning alone in an inn, my fingers skim the crystal edges of the board, and all of the fresh shallow cuts on my hands make the deep cuts inside of me a little easier to bear.

I carry the board downstairs. This inn is like any other inn. The woman/man/boy/girl behind the bar allows me to sell my services for a 10 percent cut, my services being a play of the enchanted game of legendary kings and queens. The privilege doesn’t come cheaply. No sir/ma’am, I don’t ever play myself, just like a wine merchant never samples his finest wares.

I sit on a bench nearby while they play, watching their scarred bodies heal, watching sapphire rings materialize on bony fingers. Watching careless young men break their hands and howl through lips sewn with heavy twine. After the second time this happens, I have a small pair of scissors in my breast pocket to hand to their partners. I watch players weep with happiness or horror and worry about the state of my soul, coiling like an electric blue spirit inside my chest, and then I take another sip of the spirit in my glass. I don’t stay to watch longer-term; I’m never in any one place for more than two nights.

A bitter winter follows a mild autumn, but I have very few concerns. If my board is ever stolen, which it is occasionally, it always returns back to my side. Losing my money is more of an inconvenience, but I have extra secreted away while I travel, and it’s always easy to make some more. The greatest annoyance comes from losing my horse or the banner I hang behind me when I sell my games. After one customer received an especially severe batch of cards, I suppose I was lucky to get away with a ripped banner and a few punches to the jaw.

More than once, players will read their hands and walk away from the board entirely, unheeding of my shouted warnings. Their hearts stopped before they even left the inn.

But I never force anyone to play, and I tell them all the rules upfront, and not all of the reactions towards me are negative. Sometimes, an elated girl or boy will throw themselves towards me, dizzy on achieving their dreams on a good draw, and I’ll retire to my room early with full pockets and an attractive bed mate. They’ve won themselves a love match or their mobility back or an enviable singing voice. “Just don’t play again,” I whisper into their ears as they wrap their legs around me, and they laugh.

In the early spring I share a town with some other nomadic visitors, the circus and theatre troupe The Marvelous Striped Magicians, and take the evening off to wander through their venue. The red stripes on the heavy linen of their tents ripple in the wind, and the smell of candy apples and spiced cider floats around me like music. I buy a cone of maple syrup candies from a girl painted with rainbow clouds, no older than ten. I see the fire twirlers and blade swallowers, watch their production of The Angels of Fleecewood and have my fortune read by a tattooed woman covered in inked dice. “You shall have a wealthy and lonely life,” she says, and then it is my turn to laugh.

I am the last one in the acrobats’ tent at the end of the night, having tossed a few coins onto the empty stage and taking my time to finish off my maple candy. Just as I’m about to rise, one of the acrobats drops back into the center of the tent. She bobs upside down, suspended by elastics, her long brown hair twice dusting the pale wood of the floor. “Ma’am,” she says, “while we appreciate your patronage, you can’t stay here forever.”

“I was just leaving.”

“Wait,” she says, hooking her finger for me to come closer, although it looks odd upside down. “Aren’t you the lady from The Garfont earlier today? With the cursed board game?”

“I don’t know if I’d called it cursed…”

“I didn’t mean to insult,” she says. “I was thinking it might fit in well here, if you’re looking for some company.”

The acrobat’s name is Cassio, and in addition to her skilled theatrics she is the co-owner of The Marvelous Striped Magicians. Within three months we are kissing while she’s suspended upside down, or waiting in the wings, or perched on top of her ledgers. No one will ever be Mina, but I see in her eyes how much she adores me, and she gives me a feeling of stability that I thought I’d lost forever.

Selling games of CurioQueens is better in the tents. We keep a nurse nearby in case of accidents, and there is a big painted board detailing all of the risks and disclaimers. If anything, it only makes our customers more keen. I sleep snuggled in Cassio’s wagon every night, and the rest of the troupe are eclectic and friendly.

We only play the game once, Cassio and I, the night we get engaged. She wears me down eventually, saying it’s been such a big part of my life, and shouldn’t she be included in that, too, before we marry? Which is ridiculous; I only agree because she swears on the whole company that she’ll use all the really bad cards on me, if she has to play them, that she’ll never use them on herself if she has any other choice.

Afterwards, she threads her arms around my waist and promises there was nothing really bad at all.

“What about moderately bad?” I ask.

“Only tiny bads,” she says, and I mostly believe her.

We’re married for almost four years. It would have been a lot longer, if it was just up to us, and if two of Cassio’s ropes didn’t break off their beam while she was thirty feet in the air. There was a thorough investigation which concluded no one human was at fault and ultimately resulted in phrases like “it just shouldn’t have happened” and “such terrible luck.”

I can’t even look at the CurioQueens board after that. I vanish from the troupe overnight and write to my parents in a numb cursive, asking to return home and join the family business, and then promptly set out without waiting for a reply.

In one of the more luxurious neighborhoods on my way home, I spot an advertisement printed with “Do you need support for your addiction?” above illustrations of what are unquestionably CurioQueens cards. If I ever had an addiction to that game I have been thoroughly cured of it by now, but nevertheless I find myself compelled to attend.

The support group is a little over a dozen people, almost all of who are visibly wealthy, and most of them women. One is gripping an ornate cane like a lifeline. Another sports a flesh-colored eyepatch and fifteen gem-encrusted rings. Another has a dark veil completely covering her face, with what appear to be diamonds sewn into the bottom hem. Chocolates are served in little metallic parcels, the kind you have to pull the ribbons to unwrap.

I listen to their stories and share the outline of mine, and feel very little besides a vague foolishness and unearned sense of superiority. I only played the game four times in end, despite it utterly enveloping my life. Fewer than everyone else in this circle, but still three times too many. I roll my wedding rings around in slow, methodical circles. Four times was plenty.

I am one of the first to exit when the session ends, and I’m almost outside when, “Victoria, would you wait, please,” reaches me from the other end of the corridor.

I can’t remember the speaker’s name or any of her stories. She has a long face, too distinctive to be called pretty, but that might be called handsome. As she hurries to catch up to me, she walks with a pinstripe umbrella that matches the pattern on her navy vest.

“I thought you may like to play with me some time,” she says.

I feel my eyebrows knit. “I don’t do that anymore.”

“I know,” she says. “But it’s one of the vestiges of my misspent youth, you see. That I have to play at least once a year or I’ll pass away.” Her lips twitch into a tiny smile, and I realize she must be at least fifteen years older than me. It’s the kind of smile my late grandmother used to make while saying things like, “I never did get to do that in the end, but I had a good life.”

The woman inclines her head back the way we’ve come. “Most of them in the parlor have released their boards back into the wild where they can’t hurt them anymore. Which, good for them, but you can see how that leaves me in a predicament if I don’t wish to die. You, on the other hand, have a board that follows you around.”

I tuck my sweaty hands into my pockets so I’m less likely to fidget.

“I promise I’d never hurt you,” she’s saying, “even in the slightest way.”

“That’s never been the problem,” I mutter.

But she catches my words. Her eyes are sharp. She pulls a scrap of parchment from her vest pocket and tucks it into my dress. “You don’t care about me,” she says quickly, “and I’ll die if I don’t. And you’ll get to play.” She winks, but it’s slightly pained. “Think about it.”

The parchment is still in my dress, pressed against my breast like both a promise and a cyst.

I go home.

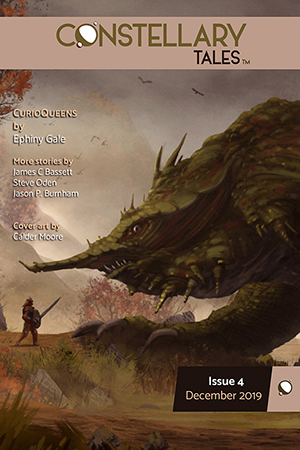

“CurioQueens”

Constellary Tales Issue No. 4, December 2019

Ephiny Gale is the author of more than two dozen published short stories and novelettes that have appeared in such publications as GigaNotoSaurus, Daily Science Fiction, and Aurealis. Her fiction has been awarded Sundress Publications’ Best of the Net award and Syntax & Salt Magazine’s Editor’s Award.