“A Scent of Roses”

By Keyan Bowes

Other houses in the village smelled of spices, of the grassy mud plastered freshly each week on the courtyard walls, of clothes drying in the wind. This one had the intense sweet fragrance of dead roses, as though someone had flung expensive attar around.

They called him Mawan, which means rose, because he was born a rosy pink instead of the usual warm earth-brown. His hair was white, not black. The child came out easily, and squinted at the harsh light. The midwife sighed with relief. Sometimes seventh births were the easiest. Other times they killed the mother.

But when his grandfather returned home, too late for the birth, he was furious. He shouted at the midwife. Were they trying to ruin his daughter? Force her to sell the last little piece of land she owned? A woman with six sons already? Sons who would have to be reared at great expense, sons who would leave.

This baby should never have been named. This baby should never have breathed. He was the seventh son with six brothers. All those mouths to feed, and for what?

So his grandfather put opium on his finger, gently picked up Mawan, and gave him the poisoned finger to suck. Did the grandfather’s face sadden as he watched the child fall asleep and never wake? Maybe. But to be a man is to do what is necessary and right. Daughters were the support of old age, the continuity of the lineage. Sons were wanderers who must be bought expensive brides, only to disappear forever to other places and lives. The fool midwife had botched her job.

After that, the house always smelled of the heightened sweetness of dying roses.

The house had been in the family for three generations, belonging before to his wife’s mother and her mother before, and now to his daughter. Every generation had added to it, extended it. It was one of the largest houses in the village, with three stories and a roof terrace and a broad courtyard behind a low wall.

Gradually, the scent percolated through the entire house. Visitors commented on the wonderful fragrance when they took off their shoes at the door and also on the excellent quality of the rose water the household served its guests. At first, they thought it was auspicious.

Two years passed, and the house saw no more births, no more pregnancies.

Mawan’s grandfather began to fret. If his daughter had no female children, what would become of her, of her lineage? They owed this to her dead mother.

Reluctantly, and with his daughter’s even more reluctant consent, he decided to start looking for another son-in-law. Her man was a good husband, devoted and honorable and obedient. But perhaps the six… seven sons he’d already given was all he could do. Perhaps he didn’t have a daughter in him.

It wasn’t easy to find a suitable second husband. People looked at the six boys and shook their heads. When it came to getting them all married, their mother would have to pay and pay. Her house’s honor demanded it. So she was already poor in prospect, even though she owned productive land and a substantial house.

Finally, they got a second spouse from an even poorer family, happy for a home where he could eat his fill, and a roof that didn’t constantly need repair. He accepted the subordinate husband role, and made sure to give the elder husband the proper respect. He showed devotion to his wife, and deference to Mawan’s grandfather. The household settled into a calm anticipation.

But another year passed with no new baby by either husband.

Mawan’s grandfather called in an augur. She’d been old when he was just a boy newly come to this village, an aged woman who knew things others didn’t, could see what others couldn’t. He paid her with good coin and welcomed her into the house.

“Why doesn’t my daughter get a female child?” he asked. Or any new child at all, he thought. “She is not past her years for children, she took no injury from earlier births. Can you tell us?”

The augur entered, sniffed the scent of roses, and immediately shook her head. No children would be born here as long as the smell remained.

They fumigated the house. They aired it out by opening all the doors and windows. They washed the floors with buckets of water containing the juice of many limes, and then with more buckets of water with washing soda. They pounded herbs into paste and smeared it near the windows, so the breeze would bring in a different scent.

They hung garlands of jasmine and other scented flowers all over the house, and burned incense in every room. Eventually, they replastered all the interior walls.

Nothing dislodged the beautiful, treacherous smell. The house was haunted by the scent of dead roses.

It was a hard decision, to leave the house that had belonged to three generations of his wife’s family. But what else could Mawan’s grandfather do? He had another house built on the land. It was small, but it was new and smelled only of the brick and plaster. The sprawling old one they sold to a family of newcomers to the village. The price they got for it helped with the cost of building its replacement.

But no sooner had they moved into the newly-built house than the clean mineral scent of the building was overwhelmed by the perfume of roses.

“It’s you,” the augur said, with pity. “The scent goes with you.”

Mawan’s grandfather knew it was true.

“Why don’t you leave it, Ba?” said his daughter. “I have six sons. The world is changing. Men can remain in their mother’s place. Look, even the Premier’s son will rule after her time, not the son’s wife.”

“The Premier’s son, yes. But what does that have to do with people like us? You still have to get your sons married. Their wives will take them away. With no daughter, who will stay? Who will care for you when you’re old? Who will inherit your mother’s land?”

The expenses were adding up, the cost of the consultations, the second wedding to a man whose family paid no bride-price, the new house. But something had to be done. His duty was to do what was necessary, what was right.

They called a priest to perform a cleansing fire-rite. Mawan’s grandfather passed his hand through the flame to purify it, then tossed in offerings of sandalwood and butter. A soothing smoke permeated the house. The priest repeated the rite on the next auspicious date, with more sandalwood, more butter, and some fine rice to feed the fire. It was all expensive, but it was essential.

But each time, once the fire was out, the rose scent returned.

The priest looked discouraged and Mawan’s grandfather sent him away.

He called another priest for an even more expensive purification ritual. But this time, when Mawan’s grandfather thrust his hand through the flame to purify it, he held it there. The tip of his finger, once dipped in opium, flared up now as if dipped in kerosene oil. The flame spread to his whole hand.

He bit down a scream of agony. The priest gasped and tried to speak, but Mawan’s grandfather cut him off and signaled to him to continue the ritual. He steeled himself to complete the ceremony before collapsing.

Over the next few weeks, the hand turned black and fell off, leaving a clean stump behind, pink as a rose against his brown skin.

Gradually, the scent faded.

On the day that he woke up and smelled the smoke from the kitchen stove, he went outside at dawn. He held up his stump and addressed his dead grandson.

“Farewell, child. Farewell, small Mawan. You may not know it, but dying before living is not the worst thing. I have done what is right, done the right thing whatever its cost to me. You will never have to do that.”

For a moment, a scent of roses.

“I was a child when I was sent away to my married home. In all the years since, I’ve seen my sisters thrice. Maybe they wouldn’t recognize me today. My wife was good to me, but she is gone. There’s no one here who is close enough to call me by my name. This is the life of a man.”

He looked over at the old house. In the distance, strangers moved around the courtyard where he used to see his wife, his children.

“My sons are married and making their own lives in other lands. Only my daughter, your mother, is left.”

Mawan’s grandfather paused, tears flooding his eyes. He was glad there was no one to see them. “I learned my duty and I have been faithful to it. Come back to us, Mawan. Come back as your little sister.”

The wind blew in off the fields, mixing the smells of the plowed field with the odor of wood smoke.

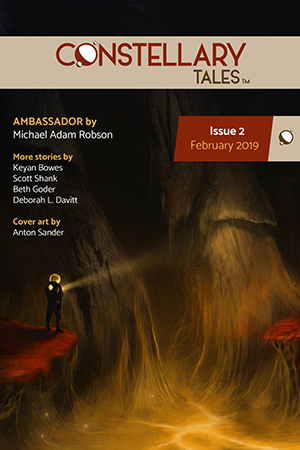

“A Scent of Roses”

Constellary Tales Issue No. 2, February 2019

Keyan Bowes is a peripatetic but San Francisco-based writer. Her works have been published in a number of web-based magazines including Fireside Fiction and Strange Horizons and in print in a dozen anthologies. She is a graduate of the Clarion writers’ workshop. Her website is www.keyanbowes.org.