“Such Stuff as Dreams Are Made On”

By Alex Shvartsman

Boys’ nightmares are flashy, but predictable and easy to vanquish.

I watch as the little boy perches atop a ten-foot-tall boulder, his arms cradled around bruised knees, his eyes wide. Gusts of harsh wind shove at him, threatening to knock his wiry frame to the ground.

A creature that resembles a rabid dog crossbred with a spider paces below. Its claws probe the smooth surface of the boulder, searching for a way up.

I whistle.

The monster turns toward me, its form blurry, the shade of its cracked-leather hide shifting constantly between scarlet and carmine. It remains still as its three sets of eyestalks focus on me. Then it charges.

I search the surreal landscape for a weapon. No matter how awful the nightmare, there is always some weapon, some tool, some way for the subconscious to fight back. Sure enough, I find it: a longsword, its hilt encrusted with emeralds, its blade both razor-sharp and blurry to the point of bleeding into the background. I raise the sword, enjoying how its weight feels in my hand as well as the pleasant tension in my calf muscles as I stand slightly crouched and face the attack. I savor the feeling of my mind in perfect control of my body.

The boy who is dreaming this world watches me as I hack and slash at the monster until it is dead on its back. It looks like a bug pinned to a block of foam, the sword driven clean through its belly and impaled into the soft earth. Its eight furry spider legs twitch in postmortem throes.

The colors of the landscape lose their intensity and fade away. Where the boulder once stood I see the faint outline of a bed, an old man’s lips stretching into a smile as he sleeps, because in his dream he is still an eight-year-old boy, and the danger has passed.

I wake up with a start. Sweat rolls down my forehead and stings my eyes, but I can’t wipe it. Advanced-stage ALS ensures that I can only fight monsters in other people’s dreams.

Doctors say the neurons inside my body are dying. They use fancy terms like dysphagia and dysarthria and spasticity—words meant to displace the hopelessness and terror of my condition with clinical nomenclature, to introduce faux reason and logic where there is none. I can’t move my limbs and it’s getting difficult to speak, but I can still think and feel, as clearly and as passionately as any healthy man. And I can still dream.

When I was a kid, I used to believe it was possible to escape from a bad dream. One only had to open their eyes wide enough to step through. I remembered those thoughts as my condition worsened and I gradually lost control of my muscles, but in my dreams—so vivid and full of color—my limbs obeyed orders issued by my mind like perfectly trained soldiers.

The dreams haunted me—the illusion of movement, of freedom, of health; the certainty that none of it was real, that even in slumber my mind wouldn’t allow me to fool myself into temporary happiness.

Until, one day, I opened my eyes wide and stepped through.

I learned to travel in other people’s dreams and nightmares as though each were a room in an enormous old mansion. Each room has its own rules, its own logic and physics. Each room is locked, separated from others by corridors made of black void, impassable and forbidding to the dreamers. But I am a ghost, floating freely through the mansion’s infinite rooms, doors and locks meaningless to me, yet never able to escape beyond the mansion’s outer walls.

My waking hours are the real nightmare: the feeling of helplessness, the pain, the bed sores and the feeding tubes. I can move nothing but my eyeballs. My stubborn brain sends futile commands to an unresponsive body, its only reward a pang of despair. I suffer through all of it just so I can fall asleep again and be free.

In dreams I walk the shores of impossible oceans, glide upon the trade winds of alien skies, revel in the strange heavens of people’s psyches. But it’s their hells I’m especially interested in.

In nightmares, people are small and scared and helpless, unable to influence events, to make things better, no matter how much they want to. They are passive observers of their own suffering, a feeling I’m too familiar with.

In every nightmare the mind conjures a weapon that can defeat it. A sword or spear to slay a monster, a branch to grab onto when drowning, a shovel to dig out from under an avalanche. The mind always provides a solution, but the dreamer is powerless to act on it. Instead they watch, paralyzed by fear just as my body is paralyzed by my disorder.

I once tried to help them fight their own battles. I waved the weapons in front of their faces, implored them to act, to stand up to their demons, but they remained impassive, unable to open their eyes wide and step through. So I began to fight for them.

I move from nightmare to nightmare, vanquishing monsters like a pugnacious Morpheus.

The first dreamscape I enter after falling asleep is a wasteland filled with serpents. They’re everywhere, crawling over each other, slinking through the dust. Each one is as long as my arm. Venom drips from their fangs, fizzling and burning on the parched ground like sulfuric acid.

I move past the snakes, avoiding the largest nests, enjoying the way my feet dance almost effortlessly across the dry earth. I search for the dreamer and the weapon.

The dreamer is the naked man in his twenties. His bare feet are cut by the jagged rocks protruding from the ground. He shambles, barely keeping away from the striking vipers, leaving a trail of blood droplets in his wake. The snakes zero in on him, approaching from every direction.

Even if it weren’t obvious by the look of terror in his eyes, I’d know he was real because his features are in focus. Everything else in the dream—the landscape, the snakes, even the sky—has a blurry quality to it, as if seen through near-sighted eyes. I survey the dreamscape. Now that I’ve found the dreamer, the weapon can’t be far. At least his nightmare is relatively barren; I think back to the time I had to search for a scythe through a thick patch of eight-foot-tall hair and I shudder.

Suddenly, a young woman steps from behind a hill. She is holding a flamethrower in both hands. She grins savagely and unleashes a stream of fire on the snakes, burning a path toward the dreamer. The flamethrower, over-the-top and almost comical, looks like the sort of weapon one might find in a Hollywood movie. That doesn’t matter, though. So long as the dreamer sees it as a thing that can help him, can save him, it will do the job. The flamethrower is blurry. The woman holding it is not.

I’m flabbergasted. I’ve never experienced a dream with another non-blurry person in it before. Is she like me? Are there other ghosts in the dreaming world? I sidestep the snakes and approach cautiously, giving her a chance to notice me so I don’t startle her. There are so many things I want to ask her, so many things I want to say. My thoughts swirl like a roiling sea. Ultimately, all I can manage is: “Hello.”

She focuses on me, and must realize that I am not a part of this dream either, because her eyes grow wide and the flamethrower hangs, forgotten, in her hands. We stare at each other, neither of us seeming to find the right words.

She finally speaks. “Are you… Are you real?”

That’s not quite the right word. We are real, but so is the dreamer. So is the danger; when the monsters punch or sting or bite me, it hurts.

“I think we’re the same.” I study her auburn hair, her hazel eyes, her high cheekbones. “Similar.” I take a step forward. “I’m Kyle.”

I wonder if the image of her I’m seeing is what she looks like in real life. I wonder how she sees me: am I a reasonable facsimile of myself, or some idealized variant? I don’t know; there are no mirrors in dreams. Even water offers no reflections.

For the briefest of moments, she hesitates. Then some of the tension drains from her. “Stephanie,” she says.

A snake lunges at her and I kick it aside. She refocuses on the serpents, uses her flamethrower to burn them. Together, we dispatch the threat and placate the dreamer. After the snakes are gone, we sit on the ground and talk until the dream begins to fade around us.

I’m afraid then, more afraid than I’ve ever been in the dream world. What if we lose each other after this dream ends? Can two ghosts travel through the mansion together?

We discover the joys of walking the dreams together, the ways of finding each other in the maze of the mansion’s rooms. Dreams are fickle and brief, each like a sandcastle in the path of an oncoming tide. We’re forced to keep moving. No matter how much time the two of us can share in any one dream, it never feels like enough.

Ghosts aren’t supposed to fall in love.

For a week, we spend every dreaming moment together. We surf the ivory clouds and splash in azure lagoons. We soak in the merriment of people’s dreams and we slay the monsters of their nightmares. We talk and laugh and hold hands.

Dying men aren’t supposed to be happy. But I am. My body continues its decline and I ignore it as best I can, daydreaming of Stephanie: her smile, her eyes, the way her head tilts ever so slightly when she listens to some goofy story I tell. It is as though I’m dead in my waking hours and come to life only when my body sleeps, and I’m with her.

She’s perfect. Eventually, I come to realize that she’s too perfect.

We share stories and talk about our favorite music and movies and happy things. But I also talk about the hospital and my condition and darker fare. Every time the conversation turns to this topic, she demurs and changes the subject.

At first, I assumed she was bedridden like me. I figured our physical impairments may be the key to unlocking our strange abilities. But she won’t confirm, won’t tell me anything about herself. It’s as though she has no life outside the world of dreams. Perhaps she doesn’t.

In every nightmare, the mind provides a weapon. I’m living a nightmare. What if Stephanie sprung from my mind, burst forth like Athena from the head of Zeus, a perfect goddess to stand between me and my suffering? If I am dreaming her, do I want to wake up? Do I want to find out?

Doubt nags at me. It seeps through, finds entry points like rain water accessing the tiniest hole in the roof. It poisons the perfection of us until I can stand it no more.

“Why won’t you open up?” I press her for details, determined to learn whether she’s real or merely a construct of my mind. “I bared my soul, but I know next to nothing about you.”

She looks past me at the shifting dreamscape. “I don’t want to talk about this.”

“Don’t you trust me? Haven’t I earned that much?” I pace, exasperated. “Are you sick, like me? How are you always in the dream world at the same time I am? Are you even real?” This last question slips out, like a bird from the cage, impossible to recapture, to take back. I immediately regret my words.

She stares at me for several heartbeats, the look of hurt in her eyes unmistakably real. I steel myself for an explosion, for her to retreat or lash out. Instead, she sighs, her eyes downcast.

“My body has been in a coma for several weeks. That’s why I’m always here. I’m trapped. Okay?”

She chokes on the words. I feel very small. The dreams aren’t her escape as they are for me. They are her prison.

“Maybe there’s something I can do,” I stammer. “Contact your family? Pass along some message when I’m awake?”

There’s the flash of anger I had expected earlier. “I said I don’t want to talk about it!” She storms off and I’m alone, trespassing in some stranger’s dream.

I don’t see her for the rest of the night. Or the night after that.

I’m dying and she’s in a coma. The time will come when one of us shows up in the dream world and the other won’t be there to greet them ever again. But not yet, not like this, not with her leaving hurt and angry at me. I must find her.

I search for her across dreams, forlorn and lost and alone. There are more rooms in the mansion than grains of sand on the beaches of the world. And yet—call it dumb luck or instinct or destiny—I find her.

The dreamscape I enter is an empty room that goes on forever. I see Stephanie, cowering on the floor by one of the walls. A bare-chested man with a nasty grin looms over her. Her features are sharp while everything else, including the man, has that blurry quality to it. This is her nightmare, and she imagines her assailant to be twice her size.

I look around for a weapon but there’s nothing in the room except the three of us, not even furniture. His hands, each as large as Stephanie’s head, are tightening around her neck. I step forward, unarmed, and shove the giant.

We fight. He pummels me with hammer-like fists and I stagger back. He’s too big, too strong. The few blows I manage to land seem only to anger him. Then I run, and he chases me across the cold cement floor.

What sort of weapon can slay a giant? I search for a slingshot, a dagger to drive through his heel, even a magic beanstalk to climb, but the room is endless and empty and featureless, and my feet are beginning to ache. In every nightmare there’s a weapon. How can this be different? Is it because Stephanie is a ghost like me? I manage to keep ahead of him as I desperately seek a solution.

The giant tires of our game and changes tactics. He turns back to Stephanie and menaces her, forcing me to return and face him. I have no choice; I step between them.

I fight back as best I can, because I must. Let him hurt me, kill me; I have little enough to lose. I’d defeated countless monsters on behalf of strangers and I won’t let this one near the woman I love, weapon or no weapon. But my resolve isn’t enough; unarmed I’m no match for the giant. For the first time, the monster might win.

Stephanie staggers to my side.

“I’m not afraid of you anymore,” she tells the giant. “You beat me and terrorized me until you put me in a coma, and I never had the nerve to stand up to you. But there’s nothing more you can do. All you are now is a bad dream.”

She stares the giant in the eye.

He flinches.

Together, we rip him apart. We tear pieces from his body like clumps of straw until he’s a mess of bloody chunks on the concrete floor. Then we sit down, breathing heavily, and hold each other, two triumphant ghosts, giant slayers who didn’t even require a slingshot.

And that’s when the realization hits me.

Every nightmarish dreamscape contains a weapon to fight against it. Perhaps the reason we didn’t find a gun, a stick, or a sword was because, in this case, I was her weapon. Does that mean I’m merely an invention of her mind, a friendly face to talk to, someone as different from her monster as possible? A tool, like the sword or the flamethrower?

Or, perhaps, ALS is my nightmare, and she’s my weapon, crafted by my mind to combat the fear and anxiety. Either way, one of us is a figment of the other’s imagination.

We hold each other and sit in silence. I ponder the nature of reality and wonder if she’s thinking along the same lines. If she has reached the same conclusion.

She dreams me, or I dream her—it doesn’t matter which. We found each other, Athena and Morpheus, two desperate dreamers sharing a connection that’s real, determined to make the most of however much time we have left together.

The dreamscape is fading around us; neither dreams nor nightmares last for long. But we aren’t bound to this place. Together, we’re free.

We clasp hands and set out in search of other monsters to slay.

“Such Stuff as Dreams Are Made On”

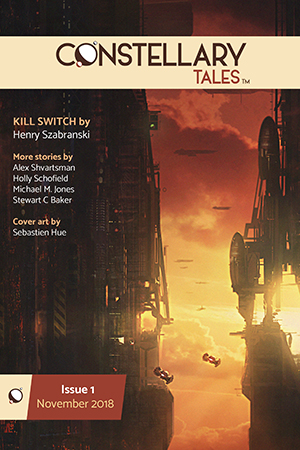

Constellary Tales Issue No. 1, November 2018

Alex Shvartsman is a writer, translator, and anthologist from Brooklyn, NY. Over 100 of his short stories have appeared in Nature, Analog, Strange Horizons, InterGalactic Medicine Show, and many other magazines and anthologies. He won the 2014 WSFA Small Press Award for Short Fiction and was a two-time finalist for the Canopus Award for Excellence in Interstellar Fiction (2015 and 2017). He is the editor of the Unidentified Funny Objects annual anthology series of humorous SF/F. His latest collection, The Golem of Deneb Seven and Other Stories, was published in 2018. His website is www.alexshvartsman.com.